Learn to write simple JSON lexer and parer

My note of learning how to implement incomplete json lexer, parser. Everything I write here is just for myself.

Table of Contents

Lexer

I wonder how to write a lexer. I know basic terminologies, there role in programming, but all of the behind the scene are blackbox to me. Fortunately, after searching for a while, I found this wonderful 3 part blog posts Writing a Lexer and Parser in Go. And in the post, the author has mentioned a talk from Rob Pike. This talk is mind blowing, it gives me insight, how genenal lexer works. And also in this talk, he introduces new technique to implement lexer, in which he calls state function.

It took me 6 or 7 times to rewatch the video. Each time, I understanded something he says. Also I found the source code for the Go template system that he talks about. Shit, first time I can look at an pro open source code and understand it, although not completely.

The idea is that maintaining the state and action for the lexer, so the lexer does not lose information which it has just found about the current state (actually I don’t clearly understand this line :D). So we use a state function, which capture the both state and do something on this state, then return the next expected state.

But first, we has to design our token structure. Here is one of theme

type TokenType int

const (

TOKEN_ERROR TokenType = iota

TOKEN_EOF

TOKEN_BEGIN_ARRAY

TOKEN_END_ARRAY

TOKEN_BEGIN_OBJECT

TOKEN_END_OBJECT

TOKEN_NAME_SEPARATOR

TOKEN_VALUE_SEPARATOR

TOKEN_NUMBER

TOKEN_STRING

TOKEN_TRUE_LITERAL

TOKEN_FALSE_LITERAL

TOKEN_NULL_LITERAL

)

type Token struct {

Type TokenType

Lexeme string

}This is the lexer.

type Lexer struct {

name string

input string

initalState lexFn

start int

pos int

width int

tokens chan Token

}And here are some important functions

func (l *Lexer) Run() {

defer close(l.tokens)

for state := l.initalState; state != nil; {

state = state(l)

}

}

func (l *Lexer) NextToken() Token {

return <-l.tokens

}

func (l *Lexer) emit(t TokenType) {

l.tokens <- Token{Type: t, Lexeme: l.input[l.start:l.pos]}

l.start = l.pos

}Runis the entry point, which was called by parser to get things tokenized.NextTokentakes the next token from the channel.emitwill put the token the lexer has done lexing into channel.

Note that the lexer will only has 2 exported function, for which the parse will call it. The rest of its methods are unexported.

Because the json spec states that json first start by value, so our initial state will be lexValue

func lexValue(l *Lexer) lexFn {

for {

switch {

case strings.HasPrefix(l.posToEndInput(), BEGIN_ARRAY):

return lexBeginArray

case strings.HasPrefix(l.posToEndInput(), BEGIN_OBJECT):

return lexBeginObject

case strings.HasPrefix(l.posToEndInput(), TRUE_LITERAL):

return lexTrueLiteral

case strings.HasPrefix(l.posToEndInput(), FALSE_LITERAL):

return lexFalseLiteral

case strings.HasPrefix(l.posToEndInput(), NULL_LITERAL):

return lexNullLiteral

case strings.HasPrefix(l.posToEndInput(), VALUE_SEPARATOR):

return lexValueSeparator

case strings.HasPrefix(l.posToEndInput(), NAME_SEPARATOR):

return lexNameSeparator

case strings.HasPrefix(l.posToEndInput(), END_ARRAY):

return lexEndArray

case strings.HasPrefix(l.posToEndInput(), END_OBJECT):

return lexEndObject

}

switch r := l.next(); {

case r == EOF:

l.emit(TOKEN_EOF)

return nil

case unicode.IsSpace(r):

l.ignore()

case r == '-' || ('0' <= r && r <= '9'):

l.backup()

return lexNumber

case r == '"':

return lexString

default:

return l.errorf("unexpected character: %q", r)

}

}

}It just looks at the current input from position to end and based on the current rune (character), decide which state function to process it.

For example, if it found the current rune is {, the lexer expect that this must be an begin array, so it call lexBeginArray

func lexBeginArray(l *Lexer) lexFn {

l.pos += len(BEGIN_ARRAY)

l.emit(TOKEN_BEGIN_ARRAY)

return lexValue

}And if it sees the rune is a digit, it expects that this must be number, so it calls lexNumber. This function was hard for me. But with the help of gpt, I managed to make it works. First we will look at the json grammar for number:

number = [ minus ] int [ frac ] [ exp ]

decimal-point = %x2E ; .

digit1-9 = %x31-39 ; 1-9

e = %x65 / %x45 ; e E

exp = e [ minus / plus ] 1*DIGIT

frac = decimal-point 1*DIGIT

int = zero / ( digit1-9 *DIGIT )

minus = %x2D ; -

plus = %x2B ; +

zero = %x30 ; 0func lexNumber(l *Lexer) lexFn {

l.accept("-")

digit1_9 := "123456789"

digit0_9 := "012345678"

if l.accept("0") {

} else if l.accept(digit1_9) {

l.acceptRun(digit0_9)

} else {

return l.errorf("bad number syntax %q", l.input[l.start:l.pos])

}

if l.accept(".") {

if !l.accept(digit0_9) {

return l.errorf("bad number syntax %q", l.input[l.start:l.pos])

}

l.acceptRun(digit0_9)

}

if l.accept("Ee") {

l.accept("+-")

if !l.accept(digit0_9) {

return l.errorf("bad number syntax %q", l.input[l.start:l.pos])

}

l.acceptRun(digit0_9)

}

l.emit(TOKEN_NUMBER)

return lexValue

}The accept function jsut comsumes the charactor if the input has that charactor. If not, nothing happens and return false. The acceptRun comsumes as many as the characters from the input. If it found rune that cannot accept, it just return.

So the idea is first, comsume - if it has any. Then try to comsume the int part. For the optional part, we can check if it has the sign of it, like the fraction with sign . and the exponent with sign Ee. If it has, we comsume the rest if fraction or exponent. Then emit the token and return basic state.

Because everything except 6 structural characters in json is value, so we return lexValue.

Parser

This also a chanllenging part. I had to read the Dragon book, found some ideas, prompt gpt, found related posts.

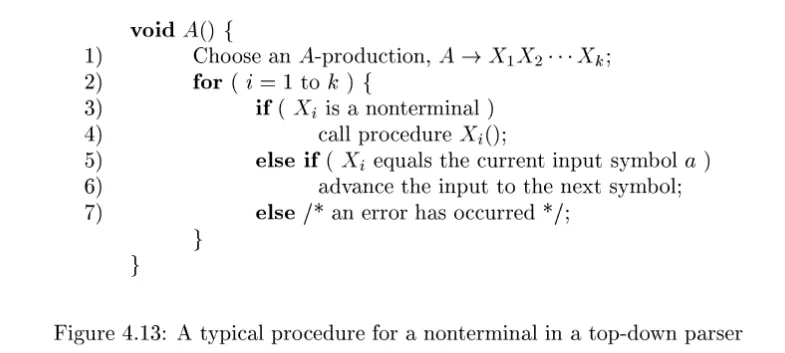

And yay, in the Dragon book, I found an simple (insufficient) algorithm called recursive descent parsing. It works in top down manner. To understand it, we has to understand context free grammar.

Finally, this is my parser

type Parser struct {

lex *lexer.Lexer

curToken lexer.Token

error error

}Again, the grammar says that (in my rewritten anltr4)

json: value;

value: object | array | NUMBER | STRING | TRUE | FALSE | NULL;

object: '{' (member (VALUE_SEPARATOR member)*)? '}' | '{' '}';

member: STRING NAME_SEPARATOR value;

array: '[' (value (VALUE_SEPARATOR value)*)? ']' | '[' ']';Applying the algo is difficult, but yeah, this is it.

func (p *Parser) parseValue() Value {

if p.hasError() {

return nil

}

switch p.curToken.Type {

case lexer.TOKEN_BEGIN_OBJECT:

p.nextToken()

return p.parseObject()

case lexer.TOKEN_BEGIN_ARRAY:

p.nextToken()

return p.parseArray()

case lexer.TOKEN_STRING:

s := String{Literal: p.curToken.Lexeme}

p.nextToken()

return s

case lexer.TOKEN_NUMBER:

v, _ := strconv.ParseFloat(p.curToken.Lexeme, 64)

n := Number{Value: v}

p.nextToken()

return n

case lexer.TOKEN_TRUE_LITERAL, lexer.TOKEN_FALSE_LITERAL:

v, _ := strconv.ParseBool(p.curToken.Lexeme)

b := Boolean{Value: v}

p.nextToken()

return b

case lexer.TOKEN_NULL_LITERAL:

p.nextToken()

return Null{}

default:

p.error = fmt.Errorf("unexpected token: %s", p.curToken.String())

return nil

}

}But if we look at it, we note that the function kinds of different from the algo. Because, in this case, we know exacly what to expect, we don’t have to choose randomly each production rule, and the grammar for value contains many alternatives, not just one rule. (check again)

Test

In this project, I also learn go testing. Just write the function TestXXXX where XXXX is the package name and put in the file xxxx_test.go.

I learn the term table-driven test, which just manually create a table of testcases and run for each of this in a for loop.

Finally, we can run go test internal/lexer/ -v.

Thought

I know this is incomplete, and is nothing compare to the programming world. But I am still proud of myself. There are so much to learn, just hope that I find joy and fun doing it. That is my ultimate goal.